Researchers from the University of North Carolina (UNC) at Chapel Hill describe how they arrived at the new definition in the journal JCI Insight.

Bladder cancer accounts for about 5% of all new cancers in the US. It is the fourth most common cancer in men, but it is less common in women.

Estimates suggest that during 2016, about 76,960 Americans will discover they have bladder cancer, and about 16,390 will die of the disease.

The wall of the bladder has four layers. Nearly all bladder cancers start in the urothelium – the innermost layer.

Next to the urothelium is a thin layer of connective tissue, blood vessels and nerves, followed by a thick layer of muscle. The outside layer – made of fatty connective tissue – separates the bladder from other nearby organs.

As the cancer grows, it spreads from the innermost layer into and through the other layers. The more layers it penetrates, the more advanced the cancer is and the harder it is to treat.

Patients diagnosed with muscle-invasive and metastatic tumors have a much poorer prognosis than patients with low-grade tumors that are largely confined to the inner layers of the bladder wall.

Signatures of immune suppression

In the study, senior authors William Kim and Benjamin Vincent, of the Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center at UNC, and colleagues found that a subtype of muscle-invasive bladder cancer shares molecular signatures with some forms of breast cancer.

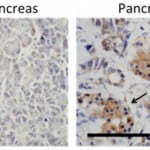

It was already known that a subset of triple-negative breast cancers expresses low levels of a protein called claudin. In the new study, the researchers show that claudin-low tumors also represent a specific subtype of bladder cancer.

The team arrived at the finding with the help of data from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA). They used the gene signatures that define claudin-low tumors in breast cancer to search TCGA data-sets obtained from 408 high-grade, muscle-invasive urothelial bladder carcinomas.

They also found that the claudin-low tumors were rich in a group of gene signatures that showed the immune system had managed to penetrate the tumors. However, despite this high immune presence, it appears the cancer cells had suppressed the immune cells by blocking their “checkpoint” molecules.

Immune checkpoint molecules are an important feature of the immune system. To ensure they attack the correct targets and not healthy cells, immune cells that do the attacking sport these “switches” on their cell surfaces. The checkpoints are activated (or inactivated) by patrolling immune cells.

However, some cancer cells find ways to use these checkpoints to avoid being attacked by the immune system. There are drugs available – called checkpoint inhibitors – that target the checkpoints to “de-repress” the immune system, and they hold a lot of promise as cancer treatments.

The authors conclude:

“These finding suggest that claudin-low bladder cancers may be particularly responsive to immunotherapy-based treatments that de-repress the immune system. Future studies will be needed to clinically test immune checkpoint inhibitors in this population.”

Meanwhile, Medical News Today recently learned how experts from around the world are making progress on agreeing a way to classify bladder cancer according to genetic and molecular – rather than cell and tissue – features.

[SOURCE :-medicalnewstoday]