As of 2014, the Burundi government has pledged that children can continue their basic schooling until grade 9. The fertility impact of this new schooling policy is potentially strong. However, there are three important elements in this story that are less well understood: what will be the magnitude of this new policy’s effect; what is the causality in the relationship between fertility and education; and what are the mechanisms driving it?

Mother and Child. Photo: Gudrun Østby, PRIO

School-age children in Burundi are enrolled in the “Ecole Fondamentale” or “Basic School”. Since the introduction of new legislation in 2014, children in Burundi now attend school for a minimum of 9 years – rather than only 6 years, as was the case before 2014. Prior to 2014, selection into secondary school was made on a competitive basis, whereby all primary school graduates who wanted to continue their education after grade 6 had to take part in a nationwide test. Each year, there were many more candidates than available seats. As of 2014, the government has pledged that children can continue their basic schooling until grade 9.

The fertility impact of this new schooling policy is potentially strong, as research in other countries has demonstrated that an increase in years of schooling is correlated with an increase in the age at which young women have their first child. However, there are three important elements in this story that are less well understood: (i) what will be the magnitude of this new policy’s effect; (ii) what is the causality in the relationship between fertility and education; and (iii) what are the mechanisms driving it?

Research on the magnitude of the impact of similar policies and the understanding of causality in this relationship has been addressed mainly for developed countries, using changes in the law as natural experiments to identify the effect of prolonged education. This research has been carried out by comparing cohorts of girls who had to go to school for longer than previous cohorts. However, very little research exists for developing countries, both in terms of causality as well as for understanding the mechanisms behind this relationship.

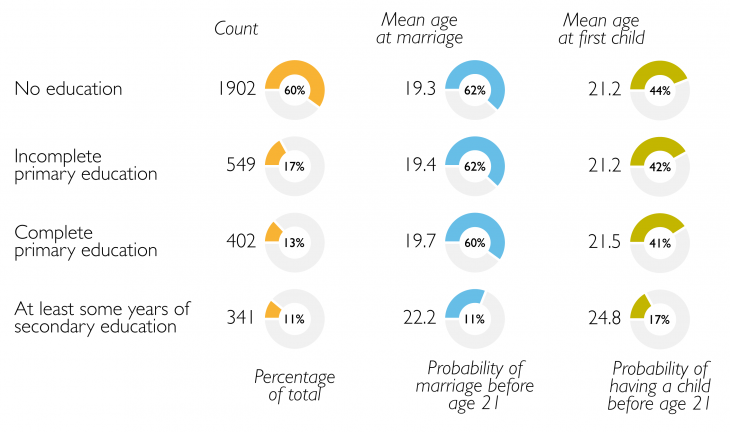

While we will only know the real impact of the new policy when the first cohort of girls has graduated, a new paper allows us to predict the answers to the three questions above. According to the Demographic and Health Survey (DHS, 2010), women born before 1980 were 21.6 years old on average when they had their first child. Of these women, 40% had their first child before they turned 21. The average age for women who did not go to school is 21.2, while it is 24.8 for women with at least some years of secondary education (see Figure 1).

Figure 1 also shows that the step that matters most is that from primary to secondary education, exactly the step addressed in the new paper.

Figure 1: Level of education, age at first child and age at marriage, Burundi. Data source: DHS, Burundi, 2010

The research we undertook in Burundi exploits the fact that, until very recently, the number of places in secondary school was limited and was much lower than the number of girls and boys who wanted access to secondary school. In 2010, the year under study in the new paper, almost 190,000 pupils competed for 35,000 seats. Those pupils who performed best in the test were allowed into secondary school.

We used the following method: in 2014, we tracked a random selection of 350 girls who had either just failed or just passed the test in 2010, at which time the girls were on average 15 years old. We know that these girls are very similar in terms of competence level, having either narrowly passed or just failed. Four years after the test, we compared their fertility. Indeed, among very similar girls, all of whom want to continue studying, one group was allowed to continue, and the other was not, based on a threshold set by the Ministry. This design is known as regression discontinuity in the literature (RDD).

We have three main results:

- Many girls who only failed the test by a narrow margin nevertheless managed to get into a secondary school, thereby disturbing the research design. Girls who fail the test often go to private schools or bribe a school director to get access. This behavioral response also indicates the strong desire to continue one’s education.

- Before the test, none of the girls had a child. Four years after the test, 14% of the girls who passed had at least one child, compared to 26% of girls who did not pass the test. This difference is statistically significant at the 1% level. In our analysis, we thus find that assignment into secondary school cuts the probability of having a child in half.

- When we consider effective treatment (thus including those girls who failed the test, but who nevertheless got into secondary school), then the proportion of girls who have a child four years after the test decreases further to 10%.

We find that assignment into secondary school cuts the probability of having a child in half

The questionnaire used in our fieldwork also allows us to shed some light on the mechanisms that drive this result. We find evidence of all the three mechanisms often discussed in the literature:

(a) ‘incarceration/discipline’: the mere effect of spending more time in school limits the opportunities to engage in sex

(b) ‘knowledge’: girls who attend secondary school are more knowledgeable about contraception

(c) ‘modernisation’: girls who attend secondary school desire a lower number of children

The findings of this research allow us to predict the fertility impact of the new education policy in Burundi before we observe the actual fertility outcomes of the post-reform graduates. The new policy will significantly increase the age at which Burundese young women have their first child, and thus substantially reduce the number of teenage pregnancies.

This research was performed independently of the new policy and had no connection with the Ministry of Education or other government initiatives in Burundi.

[“Source-blogs.prio.org”]